by Lyra Kilston

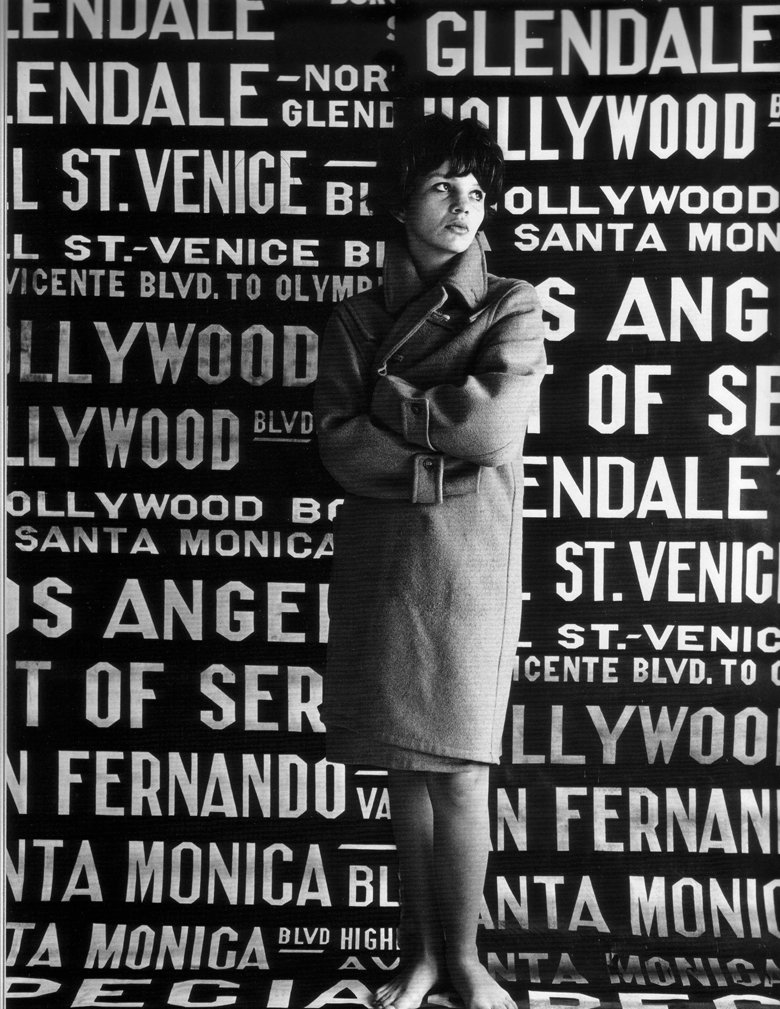

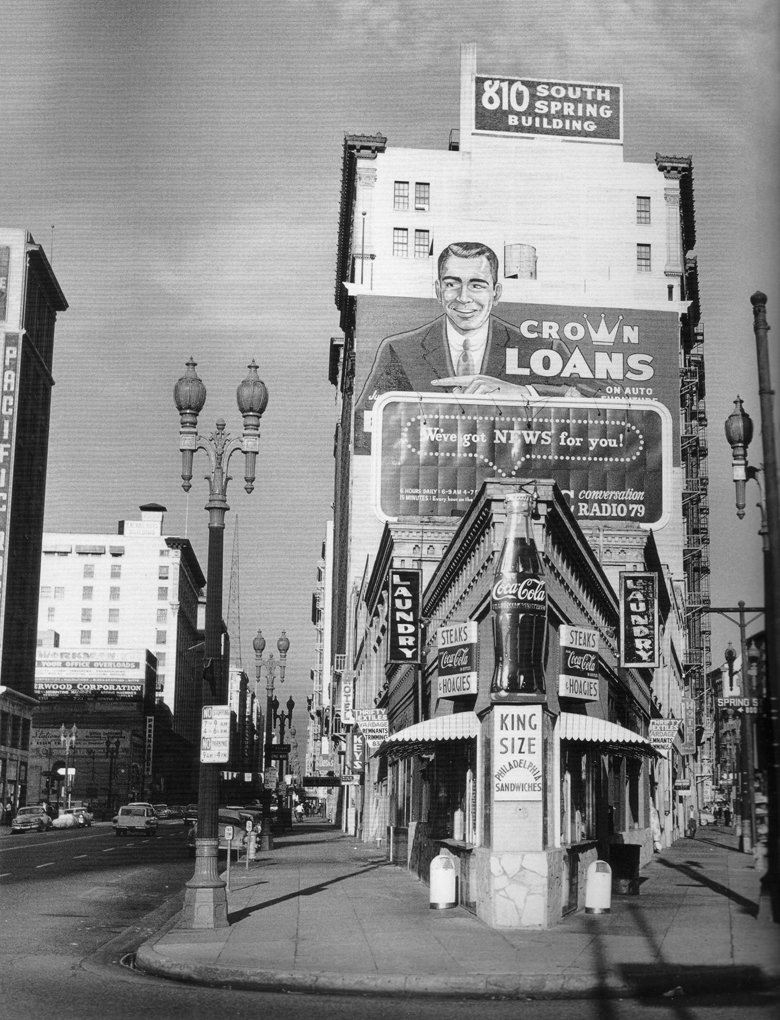

Charles Brittin (1928–2011) casually began taking snapshots in the 1950s during his rounds as a mailman in Venice, California. At the time, Venice was a sleepy, undeveloped beach community of modest bungalow homes interspersed with oil derricks along the sand. His early photographs show carnival signs on empty boardwalks, ghostly palm trees, and stretches of pale beach fringed by the derricks’ spindly scaffolding. He described the area as having “the mood of a deserted colony.”

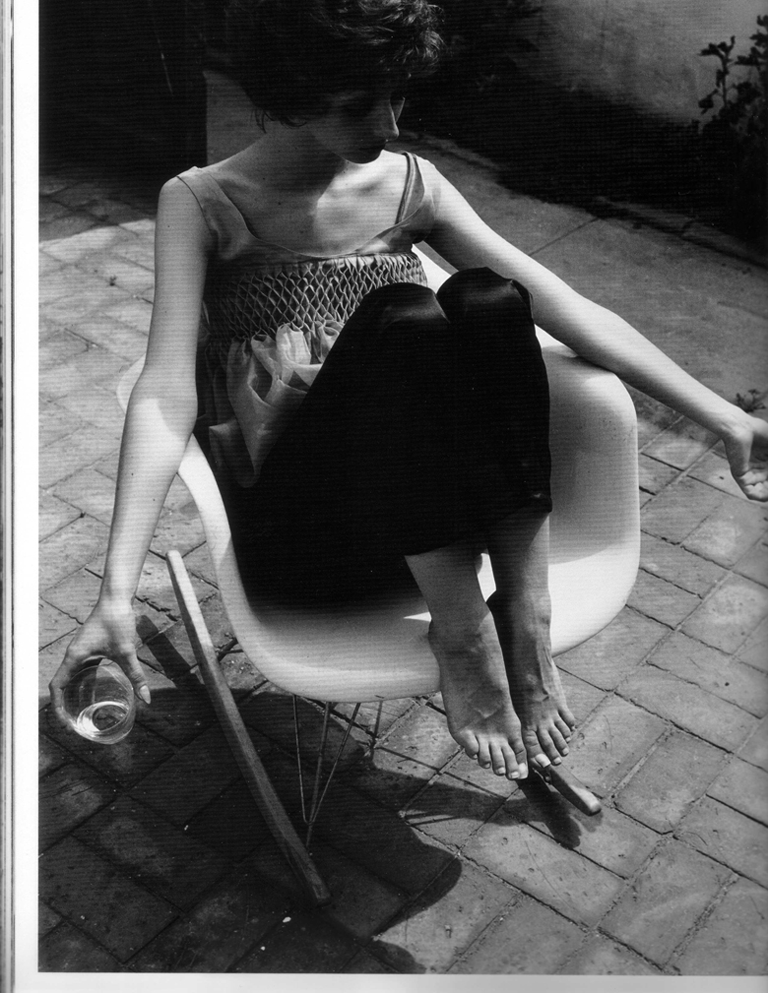

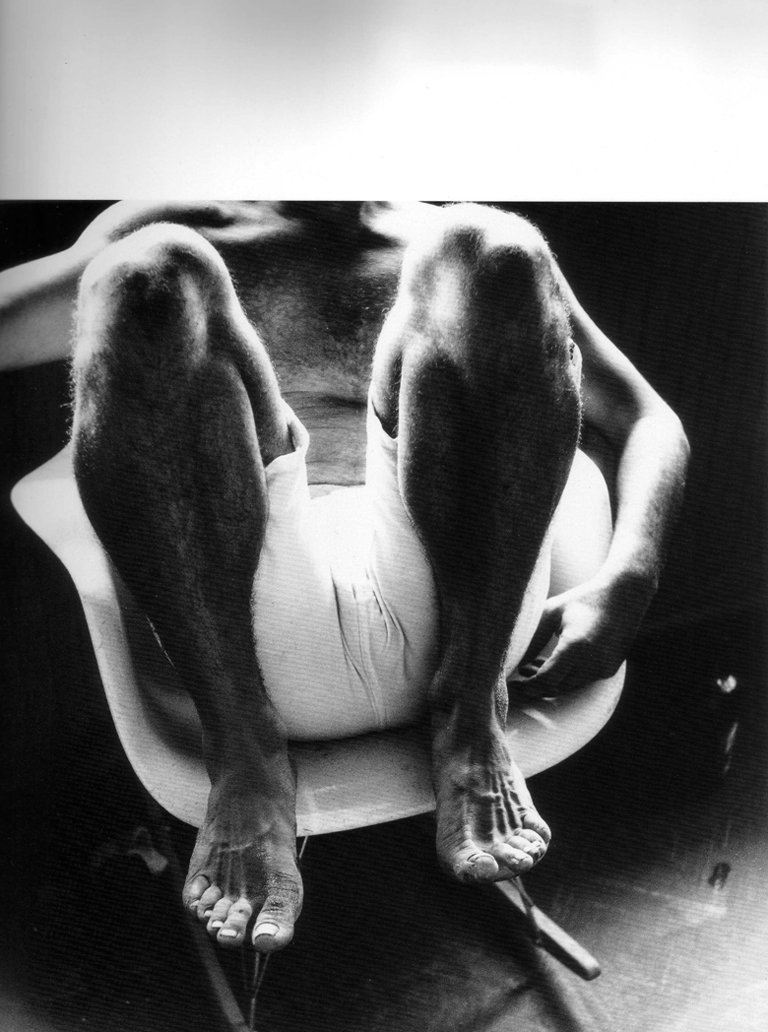

Brittin met artist Wallace Berman and his wife Shelley there, whose house was a hub for people passing through and staying for a few drinks or a few weeks. They would sit on the floor talking, making art for each other, looking at art books, and encouraging each other’s creative ideas. On this countercultural milieu Brittin reflected, “Whether it was over religion, drugs, sex or politics, everyone in our circle was alienated from conventional society. It was a group that defined itself by breaking rules, and partly by instinct, we’d formed a community that revolved around our rejection of traditional values. We weren’t interested in having careers and simply wanted to enjoy our lives and be with sweet people.”

Brittin became the unofficial house photographer for the beatnik scene around Berman’s publication Semina, a handmade magazine of poetry, collage, and mysticism, and for the Ferus Gallery, a small storefront exhibition space in Los Angeles founded by the curator Walter Hopps, the artist Edward Keinholz, and the poet Bob Alexander. The scene at Ferus—now recognized as a milestone in Los Angeles’s artistic evolution— was one of raw experimentation. Andy Warhol’s first solo exhibit was there, as well as firsts for Ed Ruscha, Robert Irwin, and Larry Bell. Brittin’s candid photos of Ferus reveal a loose, relaxed place, showing artists drinking cans of beer and goofing off. When Ferus was temporarily closed by the police for “indecency,” due to the erotic nature of some drawings on view, Brittin captured that too, photographing the handwritten sign posted in the window announcing its closure due to the “arbitrary action of the L.A.P.D.”

Brittin didn’t pursue exhibitions for his own photography; he was content taking pictures. But in 1960, Berman arranged for him to have a three-hour exhibit on a Sunday afternoon in a roofless shack he named Semina Gallery near the small town of Larkspur in northern California. Brittin’s photograph of the “gallery” shows a paint-chipped wooden structure without doors or window glass, surrounded by tall weeds. A hand-painted sign reads “EXHIBITION. CHARLES BRITTIN” and only two or three people attended. Due to a dramatic change in focus and personal illness, his work was not exhibited in a gallery again for almost 40 years.

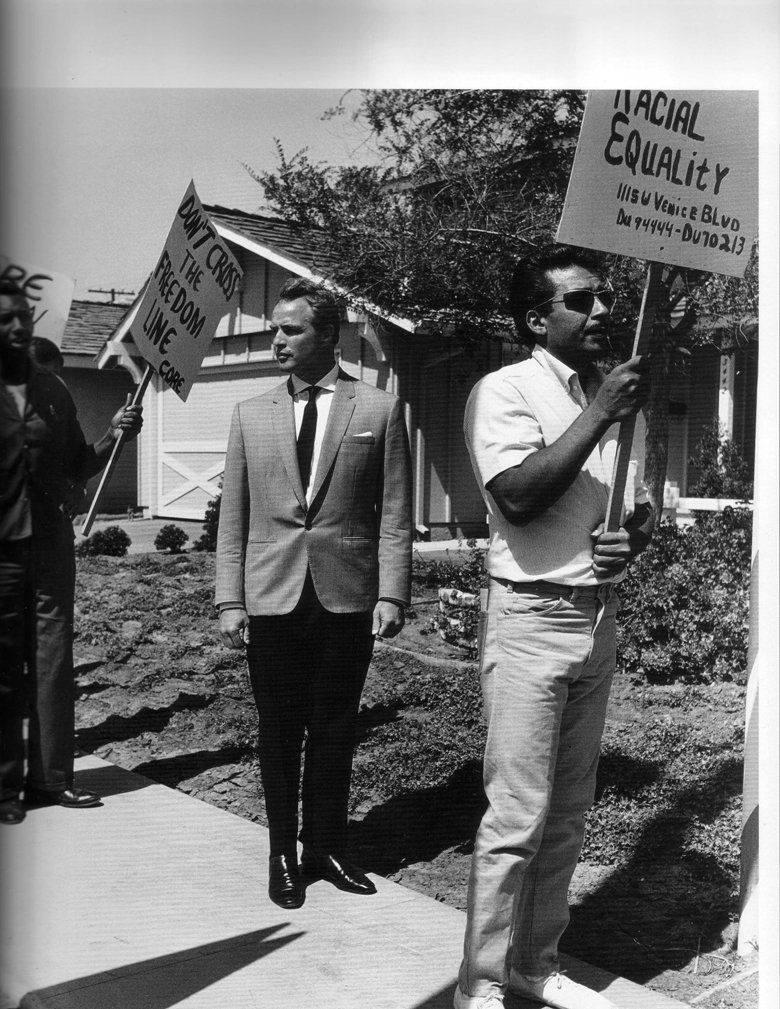

In 1962, Brittin and his wife joined the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE), a decision that changed the course of their lives. They found themselves suddenly plunged into the burgeoning Civil Rights movement and began attending protests and sit-ins, bringing along a camera. At this point, the tone of Brittin’s work took a dramatic shift, and he and his wife decided to travel to the southern United States to document the battle on the front lines.

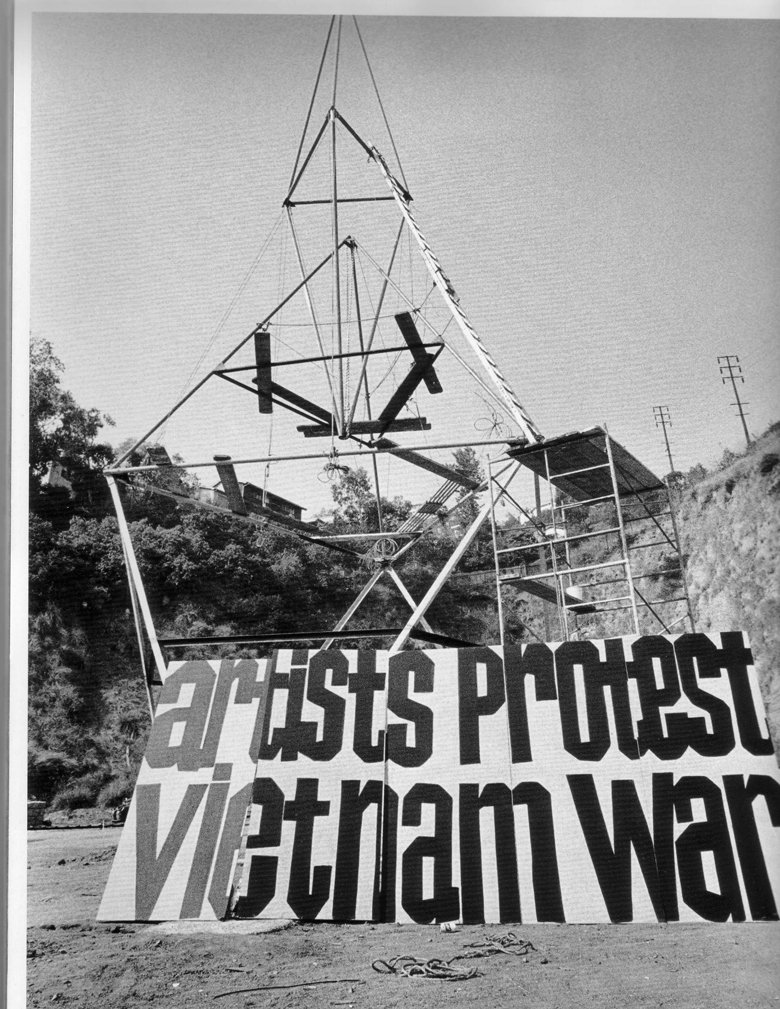

Gone were the tousled, smiling bohemians languidly shuffling about in the cool coastal air. Brittin’s camera now captured the urgency of fierce, desperate people fighting for their freedom and their lives. At one protest, a police officer grabbed Brittin’s camera and asked, “Do you have any other weapons on you?” Other weapons. His camera, recording the violence inflicted on protesters, the cruel gaze of Neo-Nazis, the stark poverty in the South, the inside of the Black Panthers’ headquarters, and the defiant spirit of protesters linking hands while facing a policeman with a rifle, had become a formidable tool. Brittin’s images of civil unrest were now published frequently in the Los Angeles Free Press and used by the Black Panthers in their pamphlets.

Brittin didn’t seek success as a professional artist, and he didn’t plan on getting so involved with the Civil Rights movement, but as he later put it, “The times demanded that I do something.” Thanks to the recent publication of a monograph of his work and several exhibitions this year in Los Angeles, Brittin’s work is reaching a new generation, revealing him to be not just in the right places at the right times, but as a photographer whose work emanates with a palpable sense of empathy and awareness.

All images are scanned or photograph ed from the book Charles Brittin: Wes t and South, Edit ed by Kristin e McKenna, Lorraine Wild , Roman Alonso , Lisa Eisner, Hatje Cantz, 2011.

All photographs ©Charles Brittin Archive