UFO, 1969 Ristorante Sherwood

by Guido Molinari

Lapo Binazzi was born in Florence, Italy in 1943. In 1967—together with Ricarrdo Foresi, Titti Maschietto, Carlo Bachi and Patrizia Cammeo—he founded UFO, a group that entered the Radical architecture scene and in 1973 set up the experimental architecture workshop, Global Tools. Following his experience with UFO, he has continued his work as an architect-artist-designer, approaching design as a pure communication phenomenon and attempting to make the artistic experience coincide with experimentation in design. He has taken part in many exhibitions including Alchimia in Florence (1981) and Documenta 8 in Kassel (1987).

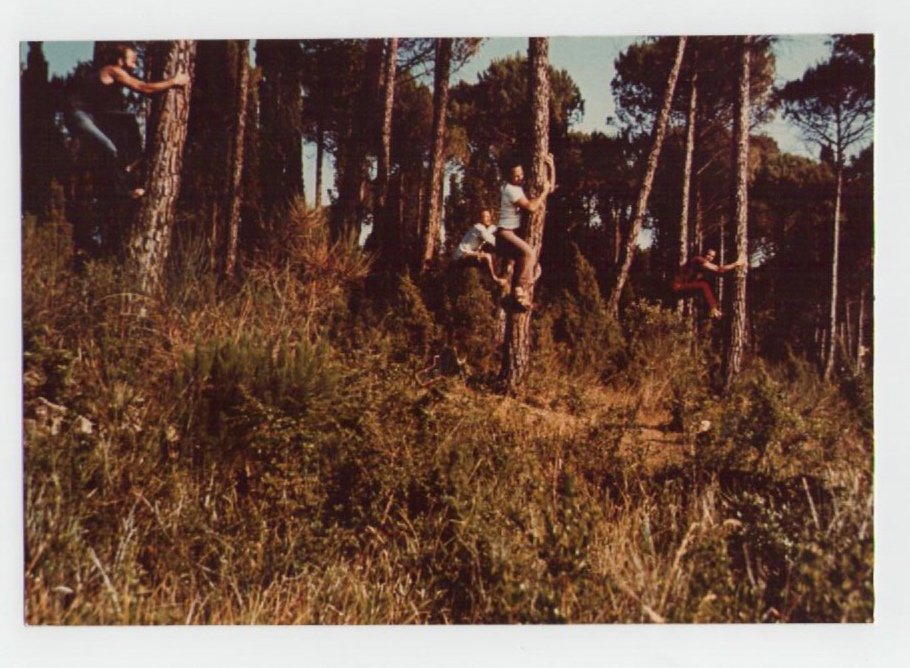

UFO, Arrampicata 1972

GUIDO MOLINARI: What exactly made you choose A.N.A.S. houses as a subject matter for your work?

LAPO BINAZZI: We were on a bus we had rented to take part in the Rieti Karnoval in January 1969. We had built a 1:1 scale inflatable Roman aqueduct that we were unable to assemble because of a snowstorm. I was sitting in a window seat jotting down ideas for the event when the bus stopped at a level crossing. I looked out of the window and found myself facing an A.N.A.S. house that seemed, simply, to be staring at me. I had a kind of illumination or epiphany and started to fantasize about it. It had recently been renovated. They were always closed. To me, they represented the archetype of Italian architecture in three colors. I began to have the desire to get to know them better, to go inside and explore their contents, even to research their various typologies.

On our return to Florence, we constructed a six-meter-high inflatable A.N.A.S. house in the courtyard of the Faculty of Architecture and started our cataloguing. The connection to the local landscape was instantly apparent, so we undertook further research on conceptual town planning, such as the 1972 Giro d’Italia. The Centrodì catalogue in 1974 was followed by many others, right up to the 1978 Venice Biennale (the year in which UFO officially split up), which we took part in with a giant poster of the A.N.A.S. house, transforming the boat into an arch and the lagoon into a paved road.

In the book Radical Architecture by P. Navone and B. Orlandoni, the authors refer to the A.N.A.S. house by UFO as “architecture of bureaucracy.” From thevery beginning, our work was focused on the processes of “tertiarization” in a post-industrial society like Italy, and the renovation of A.N.A.S. houses, which were built during the two decades of Fascism, only served to highlight this.

UFO, 1978 Biennale di Venezia-Raggi

GM: The idea of incorporating stereotypes into a design object, such as the effigy of a dollar or the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer logo, automatically connects you to the Pop Movement. What distinguished the Radical movement from that kind of research in the visual arts?

LB:The UFO group was founded in October 1967, on the wave of Superarchitettura by Archizoom and Superstudio in 1966. Pop Art first appeared at the Venice Biennale in 1964. And it was like a punch in the stomach to Mittel-European culture and art. Visual culture was suddenly preposterously in the spotlight. [Umberto] Eco taught semiology of visual communication at the Faculty of Architecture in Florence from 1965 to 1970, when he moved to Bologna and joined DAMS. UFO organized the Ristorante Sherwood installation in 1969.

In this piece, which was probably the most successful in the context of interior architecture, UFO experimented with polysemy, semantic fission, provocative connotations, and the association of ideas. All this in an n-dimensional space, no longer definable in Euclidean geometry or with the perspective of the Renaissance. In the first room, which alludes to the courtyard of a Medieval castle represented by a stone wall created in Sanderson wallpaper, one comes across suggestions of the Santa Croce choirs and of Bedouin tents with their caravanserai, around which lies a half-circle table with a Mackintosh tartan-design plastic tablecloth. On the table, surrounded by wooden thrones with ironic micro-stories painted on the backrests, are a series of distinctive “dollar” lamps. It is an almost didactic example of the relationship between denotation and connotation, between meaning and meaningful. As far as the “Paramount,” “MGM,” or the “20th Century Fox” lamps are concerned, these represent a trilogy on the re-appropriation of collective imagination represented by the dreams that the major film production companies were at that time dispensing. UFO always moved in a borderline temporal and epochal territory between Pop and Conceptual. The group introduced “Discontinuity” as an additional founding category of its creative being, managing to keep the balance between these two worlds and drawing vitality from a seemingly contradictory approach.

Lapo Binazzi, 1987 Un'idea per Le Murate-Ax

GM: Some of your work seems to precede modern solutions. In the case of Pensatoio [Think Tank] architecture, what links the shape to the function that was assigned to it?

The Pensatoio project—a model of which is preserved by FRAC in Orlèans, as are the original UFO drawings which were then channeled into the UFO thesis of 1971—was not exactly conceived for that purpose, but for restoring a barn. The idea of substituting solids with voids, of placing the pigeon-house rooms—four rooms and two bathrooms—on the outside of the glass structure, of creating a large sitting room with a fireplace and a large open-plan kitchen on the ground floor, effectively anticipates the concept of “disjunction” by B. Tschumi. In any case, it creates an n-dimensional space in which the 360° fruition of the space itself prevails over the laws of perspective. As in Sherwood Restaurant, the architectural space is “narrated” in a story in which the spatial coordinates are semiotic[1] and go on to comprise the activities and performances of UFO as, in the words of A. Branzi, “autonomous actions.”

[1] See the above-mentioned concept of “semantic fission.”

GM: Some of your work has been characterized by a clear conceptual approach, almost drawing on irony. Why were you swimming in sync or climbing trees?

LB: Nuotata in Castel Ruggero [Florence] in 1972 consisted of UFO members swimming in line, back to back, spread out like a flying bird, etc., giving a variable geometry both to the surrounding nature and to the performance, which was, in itself, a form of architecture. It was a parody of Mao Tse-tung swimming in the Yangtze River. The project, preserved through a series of photos, is the conceptual proposal of a correctly implemented action of vitality. The same applies to the Arrampicata project. The choral and collective action stimulates group creativity in a union of consciousness.

It was the same year, 1972, that the cover-photo for issue no. 376 of Casabella magazine was taken, in which UFO is gathered under an electricity pylon, making Chinese-style faces. Inspiration for this came from the magazine Illustrated China, which I received on a regular basis, in which pictures of electricity pylons, or other state constructions, were portrayed as examples of modern ideology. Our architect and folk singer friend Antonio Infantino was an exceptional presence in these projects.

GM: The Pinocchio book, or the memorable Servizio del Dott. Caligaris, lead to the definition of new shapes to challenge familiar, everyday objects. In this sense, did “Second Futurism” provide you with a reference point?

Pinocchio Triangolare is an artist’s sketchbook project that I undertook alone in 1991 and which has since become a cult collector’s piece found in a number of libraries, including the National Library in London and the National Library in Florence. It was inspired by a proposal made by Fabrizio Gori to create a catalogue of the work of five artists on Pinocchio. My contribution consisted of a conceptual and computerized reinterpretation of a Futurist Pinocchio. This is because I have always considered Pinocchio both a predecessor of Futurism and a symbol of the end of the 19th century.

Servizio del Dott. Caligaris is a work I carried out in 1989 following my participation in the 1987 “Un’idea per le Murate” architectural competition, created for the restoration and reclaiming of the former prison in Florence. I counted on the valuable collaboration of C. Vannicola and his partner P. Palma, two young architects who later became excellent and well-known designers. It consisted of a silver tea set made by the Florentine company Pamploni, with whom, in fact, I still work today. It was another example of work that expressed an attempt to create expressionistic shapes and inclined surfaces and spaces, which, although less reassuring, were also less boring and banal than everyday objects.

Considering that more than twenty years had passed between the first Radical architecture revolution and the period in which these objects were created, and also considering that from 1975 the UFO “new crafts” workshop set out to renew the suffocating, repetitive and consolatory offerings of traditional crafts, I think it is fair to speak of a Second Futurism, especially as I was involved directly, as I had been in the previous Radical avant-garde. In fact, my 1997 artist’s sketchbook is called “The Radical Reconstruction of the Universe,” which later became both the name and the content of my website.

UFO, 1971 Salone del Mobile Milano

GM: Bicycles and your hat are recurrent images in your work. Are these autobiographical references?

LB: UFO used bicycles for its actions. In 1971, its first Giro d’Italia was held at 9999’s Space Electronic in Florence during the Festival of Conceptual Architecture. Many international groups took part, as well as artists who were close to our Radical research, such as G. Chiari and R. Ranaldi. UFO wore the t-shirts of Italian cycling champions, created specially by the stylist Chiara Boni and also sold in her shop “You Tarzan Me Jane” in Florence, together with t-shirts of football teams. The point was to create a kind of imposing paraphrase on clothing as a provocative alternative to the status-symbol garments of the fashion system. Giro d’Italia became a telling element of a territorial recognition, which offered itself as an urban concept and performance as an alternative to the Superarchitettura of Archizoom and Superstudio. Other Giri d’Italia followed, the next in 1972 in Chianti, of which a video was made and copies are preserved at ASAC in Venice and in the Art Tapes 22 collection in Florence. A UFO performance in 1974 for the Contemporary Exhibition in Rome involved an attempt to unearth suburban, fenced-off, concealed and secret environments, such as electricity pylons, greenhouses, etc. Anyway, racing bikes do have an autobiographical element in them. As does the fisherman’s hat, which I use as a symbol of my personal style and to protect my head.

GM: In retrospect how would you say that the Radical movement influenced the outcome of design?

LB: Undoubtedly, Radical design has greatly influenced Italian and international design. The power of its sometimes even extreme research has contributed to changing the perception of design, which until then had seemed exclusively linked to the specific concept of “industrial Italy” and which, by the mid-1960s, was beginning to wear out. Visual arts were challenged, opening up new possibilities and attracting international designers such as Stark, Arad, Coates, and an infinite number of others to work with Italian companies.

GM: In those years, what was the relationship between the requirements of the client, when there was one, and your creative freedom?

LB: Radical design has always moved in an autonomous way in the attempt to give visibility to objects derived from new behavior, such as the Superonda Sette by Archizoom for Poltronova, the Zucca by Superstudio for Giovanetti, and the objects created from UFO installations such as the Lampada Dollaro. To these I would like to add Dreambeds by Archizoom, which were never put into production, Camel-sofas by UFO for Bambaissa, and countless others that still today would be worthy of being put into production, perhaps more as visual objects than elements of design.

And this is where utopia lies. Like imagination, it manages to produce and create very daring elements. Without being commissioned as such, these pieces set off a mechanism of desire that is typically urban and with the philosophical libertinism of the Enlightenment. It is not therefore true that one is a follower of the Enlightenment movement only within the boundaries defined by perspective, by rationality, and by tendency. In conclusion, one could say that the principal commissioner must be the artist or designer himself.

GM: How has the world of contemporary art been able to understand and channel the innovative suggestions you made during those years?

LB: The relationship of Radical design with visual arts is quite complex. Even if critics like A.B. Oliva, G. Celant, L.V. Masini and E. Pedrini took on, from the very beginning, the task of making the theory of Radical architecture acceptable and widespread, together with E. Ambasz, T. Trini, Gillo Dorfles and many others, one has to wait until the end of the second millennium for the acceptance of Radical architecture and design in international museums like MoMA, Centre Pompidou, Centro Pecci, Maxxi, etc.

I don’t believe we have reached a theoretical equality between design and visual arts, but we are getting there, even in terms of prices. And in the end, that was the aim of our unstoppable desire to go beyond the disciplinary boundaries, to create a truly free approach. At times the gratuitousness of art has acted as an exceptional stimulus for the freedom of visual research, but at other times Radical design has demonstrated that it is on the same level, or higher, in terms of coherence of its theoretical intention, even in the presence of solutions tied to function.

UFO, 1973 Copertina Casabella